1877

The Readjuster Party is founded, campaigning on working to reduce the grand debts owed by the state of Virginia (Lause 2015). Supported by much of the Virginian working class, the Readjuster Party was one of the first semblances of a specifically working class affiliated political entity post-Civil War (Lause 2015). Investing greatly in education in places where its candidates managed to get elected, it raised funds for both Virginia Tech and Virginia State University, the latter of which was a black institution at the time (Rachleff 1989). Also abolishing the poll tax and public whipping post, the party lost unprecedented electoral holds in 1883, and would fold in 1885 (Lause 2015).

“The Facebook” Launched By Mark Zuckerberg

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Tum Torquatus: Prorsus

1880

First ever boycott in Richmond

Workers of Liebermuth and Millhiser Cigar Co. instituted a boycott in protest of their unsatisfactory working conditions and aspirations for better pay and more benefits (Lause 2015).

Acquires Facebook.com Domain Name

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Quo modo autem…

1884

The Knights of Labor come to Richmond

Founded in Philadelphia in 1869, following a slow growth, the Knights of Labor suddenly exploded into a national working class operation (Fink, 2008). In Richmond, it began as a white labor institution, but soon began to incorporate black workers (Fink, 2008). As there were no clear foundational lines concerning racial integration within the organization, the allowance of black workers into the Knights of Labor was a widely debated topic in Virginia (Fink, 2008). The 1886 national convention of the Knights of Labor, in Richmond, would prove vital in determining the role of black workers within the organization, but all progress made for the inclusion of black workers in the Knights of Labor began to dwindle away as the organization saw new leadership in the late 1880s (Gerteis 2007). As the proportion of membership and vital roles within the organization had become so prominently black, in moving to make the Knights of Labor an institution for white workers, white leadership of the organization would prove to handicap their own labor efforts as the tactics used to expel black workers played a large role in dismantling the entire organization (Gerteis 2007). By the mid-1890s, the Knights of Labor played only negligible at best importance in any part of the United States in which they had once held prominence (Rachleff 1989).

ConnectU Settlement – Facebook Paid $65M

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Stoici scilicet. Restinguet…

1885

Convict labor is put to an end in the Richmond barrel-making industry. Convict labor, an attempt at prolonging the sorts of slavery prominent in Virginia just decades before, due to the manner in which black people were targets for inclusion in this program, came to an end in the Richmond barrel-making industry due to a Knights of Labor-led prolonged and mass boycott of Haxall-Crenshaw Flour, the largest purchaser of Richmond-made barrels (Fink, 2008).

Purchased FB.com Domain – $8.5 Million

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Nescio quo…

1886

The Richmond Typographical Union, allied with the Knights of Labor, unionizes the last remaining non-unionized print office in all of Richmond, and goes on to focus its efforts in Alexandria and Petersburg (Fink 2008).

Timeline Heading

This is Timeline description, you can change me anytime click here

1886

Now roughly 700,000 strong nationwide, the topic of racial integration is a widely discussed point at the Knights of Labor National Convention in Richmond (Gerteis 2007). Largely aided by the presence and words of Frank Ferrell, a prominent black representative within the Knights of Labor from New York City, it was made known that the Knights of Labor was welcome to black membership as it had largely been in years prior and which had led to the majority of districts within the organization being integrated (Gerteis 2007). Words from Grand Master Workman of the Knights of Labor, Terrence Powderly, also proved helpful to the cause (Gerteis 2007). The departure of Powderly as Grand Master Workman in 1893 would prove to be a final nail in the coffin of the preservation of integration within the organization, as the following leadership was not nearly as sentimental towards the black working class of the United States, nor realized the importance of the black working class in a mass labor movement (Rachleff 1989). John Hayes, Grand Master Workman of the Knights of Labor from 1901 to its dissolution in 1917, throughout all of which the organization was obsolete with no hopes of resurgence, proposed deporting the entire black population from America, clearly in extreme contrast to Powderly’s progressive views (Rachleff 1989).

Timeline Heading

This is Timeline description, you can change me anytime click here

1890

Following its founding in 1888, the International Association of Machinists is headquartered in Richmond (Lause 2015). Still around today, the organization now goes by the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers, is headquartered in Maryland, and has over 500,000 workers within its ranks (Lause 2015).

Timeline Heading

This is Timeline description, you can change me anytime click here

1910

Created in 1891, the headquarters of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers are moved to Richmond (Lause 2015). The IBEW is now based in Washington, DC, and represents nearly 800,000 workers (Lause 2015).

Timeline Heading

This is Timeline description, you can change me anytime click here

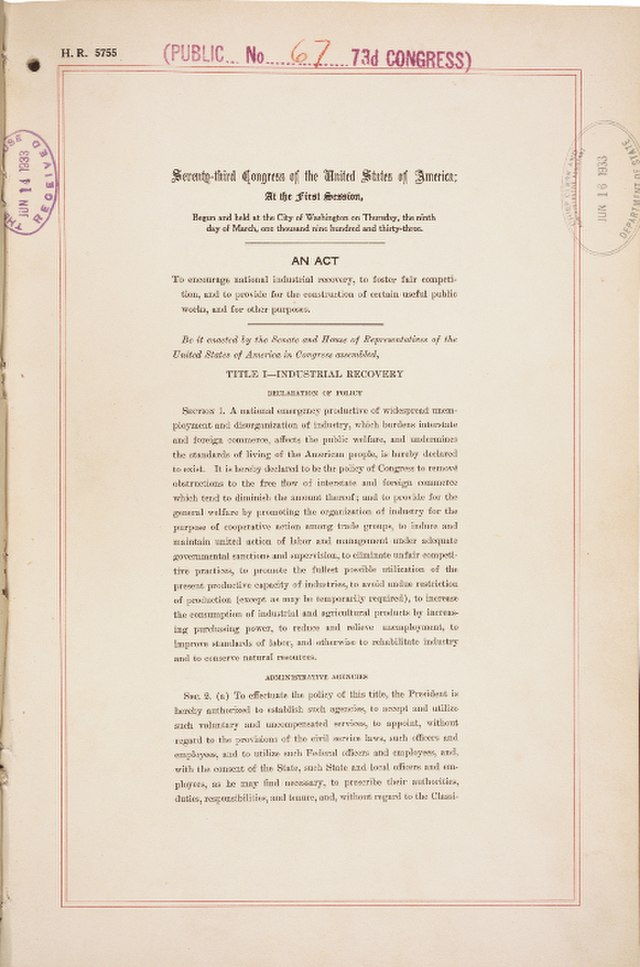

1933

The National Industrial Recovery Act is passed in congress, granting workers’ rights to organize and participate in collective bargaining, and guarantees protection against discrimination practiced by employers against employees who join unions (Love, 2007). This is a major win for labor efforts across the nation, including within Richmond.

Timeline Heading

This is Timeline description, you can change me anytime click here

1933

The Tobacco Workers International Union presses employers at Brown & Williamson Co. in Richmond to sign a contract that greatly benefits workers represented by the union (Love, 2007). This contract includes a union closed shop, check off, and a pay increase towards all of the 1000+ employees at Brown & Williamson Co (Love, 2007).

Timeline Heading

This is Timeline description, you can change me anytime click here

1937

Several hundred striking workers at the Carrington and Michaux tobacco plant in Richmond win eight-hour days, pay increases, and the recognition of their rights to collective bargaining (Love, 2007). This is the beginning of a series of successful black labor movements in Richmond as just a month later, hundreds more black workers at the predominantly female I.N. Vaughan tobacco plant go on strike and win reduced hours as well as increased pay (Love, 2007). Later that year, several hundred more black workers at Tobacco By-Product and Chemical Corporation go on a prolonged strike that results in paid time off, increased wages, reduced hours, and guaranteed overtime pay (Love, 2007).

Timeline Heading

This is Timeline description, you can change me anytime click here

1938

Following carefully planned and extensive organizing, labor activist Louise “Mama” Harris leads her coworkers as picket captain in an especially hard-fought prolonged strike against the Export Leaf Tobacco Company, that results in paid time off, a union due check off system, and increased pay (Love, 2007). These successful black labor movements inspired further actions by the black working class of Virginia throughout the remainder of the 1930s as well as the 1940s, even acting as a precursor to black power and liberation movements that would sweep across America throughout the 1950s, 60s, and into the 70s (Love, 2007).

Timeline Heading

This is Timeline description, you can change me anytime click here

Citations…

Fink, Leon. “‘Irrespective of Party, Color or Social Standing’;: The Knights of Labor

and Opposition Politics in Richmond, Virginia.” Taylor & Francis, 3 July

2008,

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00236567808584499?

journalCode=clah20.

Gerteis, Joseph. Class and the Color Line Interracial Class Coalition in the Knights

of Labor and the Populist Movement. Duke University Press, 2007.

Lause, Mark A. Free Labor: The Civil War and the Making of an American Working

Class. University of Illinois Press, 2015.

Love, Richard. “In Defiance of Custom and Tradition: Black Tobacco Workers and

Labor Unions in Richmond, Virginia 1937–1941.” Taylor & Francis, 28 Feb.

2007,

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00236569400890021?

journalCode=clah20.

Rachleff, Peter J. Black Labor in Richmond, 1865-1890. University of Illinois Press,

1989.